As explained earlier, the goal of this blog is to spread best practices as well as practical tools and techniques for SMEs to apply Revenue Management to their business. Recalling the principles mentioned in our previous article, one of the common reasons for the implementation of a RM system, is the management of the perishable aspect of a given service, and the high opportunity cost of missed sales. If, on a Saturday night, a theater gets full for a certain movie, it will miss the next sales forever – if we assume the potential customer may not buy a ticket for another movie, which is often wrong.

This leads to a crucial aspect linked with missed sales, a high seasonality factor combined with limited resources: Peak Loads. Peak loads have to be managed in order not to miss any chance to maximize revenue for the market (time period/service). For example, you cannot create instantly new seats or remove them in a theater, so a given capacity has to be optimized. In this article, we will share with you a basic pricing tool that we have developed to help you to manage your peak loads – if your business is concerned. As we will see this requires a minimum of demand forecast, and an idea of your customers’ behaviors versus price changes.

The structure of costs is a good reason for implementing RM techniques: the high share of fixed costs (buildings, maintenance, staff…) makes the business harder to operate and the anticipation of demand key. Indeed, if the variable costs per unit are low, maximizing profit implies maximizing revenue. It is a major aspect, since a common Peak Load strategy is to use the peak period revenues to compensate the losses – if any – generated when business is slower, as the capacity is hardly modifiable over time.

With those high level features and “pre-requisites” for implementing a revenue management system, we can already draw a series of activities where Peak Load pricing strategies are applied, or could be applied:

- Rental businesses

- Hairdressers (explained by Robert Cross in his book)

- Parking lots

- Internet cafes (experimented in 1999 by Easygroup in the UK)

- Theaters and concert halls

- Public meetings and events

- Public meetings and events

- Road toll

Peak loads or the first critical issue addressed by a RM system

Let’s start with the core subject. Peak load is a key issue, which motivated the creation of RM systems. Is a corporation able to identify peak loads patterns, or not? If yes, can it change the demand to avoid these peak loads? Often, historical data from past cycles or knowing the market patterns are enough. Some companies usually know their customers well, other, have to go through market studies and business intelligence reports to identify customers’ cycles…

Knowing your peak load, when the demand tends to exceed the capacity, is crucial. Even better, is being able to steer your demand and volume. Hairdressers in France for example, found a way to avoid high Saturday afternoon peak times, by opening until late evening during weekdays. Does it work? Does it deter customers from coming massively on Saturdays? Is that enough, or would a price difference spread the demand over more days of the week? Probably, as it is the case in the hospitality industry, where part of demand is transferred to a time period when booking level is low.

On a day to day basis, you don’t take your decisions based on a scientific datamining of past customer behaviors and market information. Indeed, most operational decisions are taken in a degraded situation, without relying on precise quantitative data: a certain level of uncertainty is assumed.

An interesting article article from James Dana, Using Yield Management to shift demand when the peak time is unknown, highlighted the capacity of an organization to manage unanticipated demand. “The equilibrium price dispersion can efficiently shift demand and lower capacity”: the article demonstrate that when companies set prices in accordance to demand at time t, they are able to steer demand. However corporations must be able to set probabilities for sales at a price X and Y (where X≠Y), and then be able to set these prices (X and Y), with the overall constraint of making a profit.

Let’s remind that this constitute a win-win situation, where both the consumer (who pays less, against a tradeoff regarding the time of consumption) and the producer (who achieves a greater profit) increase their surplus.

Our simplified model

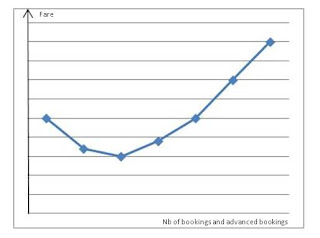

We have designed and integrated a simplified peak load management model to this article(see below). From a given capacity and unique price, the model calculates the optimal pricing for the peak and non-peak periods. At the center of this revenue optimization model is the concept of price elasticity. The price elasticity measure the responsiveness of demand to a price change, basically: % change in demand divided by % change in price. We will write a further article on price elasticity estimation. For the moment, we take a basic linear elasticity in our model, which we estimate from your information and a rule of thumb (see below).

This model is highly simplified, and overlooks several important elements. It assumes linear price elasticity, hypothesis that we will review within few days. The results should be put in perspective, taking the following issues into account:

- The competitors reaction

- The size and concentration of the market

- The overall consequences on the marketplace: if every player apply the same pricing strategy, will that expand or shrink the market overall?

- A seasonality pattern that adds to the periodic peak load pattern

Next items to come soon: Skimming strategies, Profit Management, Dynamic pricing and effects on the organization, and many others! Any feedback on the blog is greatly appreciated!

Peak loads or the first critical issue addressed by a RM system

Let’s start with the core subject. Peak load is a key issue, which motivated the creation of RM systems. Is a corporation able to identify peak loads patterns, or not? If yes, can it change the demand to avoid these peak loads? Often, historical data from past cycles or knowing the market patterns are enough. Some companies usually know their customers well, other, have to go through market studies and business intelligence reports to identify customers’ cycles…

Knowing your peak load, when the demand tends to exceed the capacity, is crucial. Even better, is being able to steer your demand and volume. Hairdressers in France for example, found a way to avoid high Saturday afternoon peak times, by opening until late evening during weekdays. Does it work? Does it deter customers from coming massively on Saturdays? Is that enough, or would a price difference spread the demand over more days of the week? Probably, as it is the case in the hospitality industry, where part of demand is transferred to a time period when booking level is low.

On a day to day basis, you don’t take your decisions based on a scientific datamining of past customer behaviors and market information. Indeed, most operational decisions are taken in a degraded situation, without relying on precise quantitative data: a certain level of uncertainty is assumed.

An interesting article article from James Dana, Using Yield Management to shift demand when the peak time is unknown, highlighted the capacity of an organization to manage unanticipated demand. “The equilibrium price dispersion can efficiently shift demand and lower capacity”: the article demonstrate that when companies set prices in accordance to demand at time t, they are able to steer demand. However corporations must be able to set probabilities for sales at a price X and Y (where X≠Y), and then be able to set these prices (X and Y), with the overall constraint of making a profit.

Let’s remind that this constitute a win-win situation, where both the consumer (who pays less, against a tradeoff regarding the time of consumption) and the producer (who achieves a greater profit) increase their surplus.

Our simplified model

We have designed and integrated a simplified peak load management model to this article(see below). From a given capacity and unique price, the model calculates the optimal pricing for the peak and non-peak periods. At the center of this revenue optimization model is the concept of price elasticity. The price elasticity measure the responsiveness of demand to a price change, basically: % change in demand divided by % change in price. We will write a further article on price elasticity estimation. For the moment, we take a basic linear elasticity in our model, which we estimate from your information and a rule of thumb (see below).

This model is highly simplified, and overlooks several important elements. It assumes linear price elasticity, hypothesis that we will review within few days. The results should be put in perspective, taking the following issues into account:

- The competitors reaction

- The size and concentration of the market

- The overall consequences on the marketplace: if every player apply the same pricing strategy, will that expand or shrink the market overall?

- A seasonality pattern that adds to the periodic peak load pattern