Contrary to price skimming, penetration pricing involves selling products at a lower price relative to direct competition. The underlying idea is to "penetrate" the market, i.e. gain a solid market share and build a base of loyal customers. From this base, prices are then progressively increased to reach the final price.

We are surrounded by examples from the perishable goods industry. Let’s use California Kitchen frozen pizzas: from August to October, Yoann paid $4.99 for a pizza (he does not eat healthy) with his Ralph's card, versus an advertised regular price of $6.99. Then, from October to September, he paid $5.99, and received a $1 coupon per pizza purchased - the advertised regular price remained at $6.99. In January, he paid $5.99, but did not receive a coupon (he then stopped buying those pizzas). We can infer that California Kitchen will charge $6.99 a pizza relatively soon!

Such a strategy is likely to be carried out successfully if the following elements are observed:

- The company must be operating in a relatively elastic portion of the demand curve (so that the lower price result in a significant amount of additional sales)

- The possibility of economies of scale. Just like revenue management in general, penetration pricing is justified by the ability to optimize capacity, and therefore lower unit production costs

- As mentioned in previous articles, the corporation has to make sure that price is a "non-signal" of quality, in order to prevent a drop in sales!

- The company must to make sure that its supply chain will support the additional sales.

Admittedly, if the product sold is not differentiated enough from competition, then this strategy can trigger a price war, destroying any advantage that the corporation may get out of it.

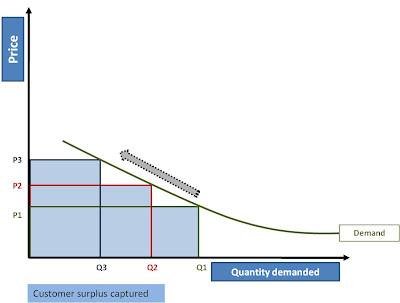

Customers’ loyalty is a key element in price penetration. As we can see on the graph below, the strategy takes advantage of a solid customer base built charging a low price (versus direct competition) to price-sensitive customers. The demand curb is bowing progressively (from t1 to t2, and t2 to t3), illustrating the effect of loyalty on demand - which becomes less price sensitive. The penetration strategy takes advantage of that situation, charging a higher price (in t2 and t3) to a less elastic demand.

The following graph (below) offers a comparison. The company charges the exact same prices in t1, t2 and t3 as on the above graph. However, it does not benefit from a “loyalty effect”: The demand curve therefore remains the same through time. In this case, the company’s goal becomes maximizing revenue/profit from a given demand, and it does not have any incentive to purse this strategy.

Freebie marketing (Complementary goods)

Some corporations make a great use of penetration pricing, using this strategy to boost complementary products' sales. The main product is sold at a low price (often at a loss), in order to ensure a recurrent revenue stream from the associated consumables.

This business model where one item is almost given away in order to increase the sales of a complementary good, is known as freebie marketing. Freebie marketing is not new. As Alice Tisdale Hobart explains in Oil for the lamps of China: in order to expand to China, Standard Oil gave 8 millions of kerosene lamps away (or sold it at rock-bottom prices). Doing so, it created a demand for kerosene among Chinese customers, who would soon buy their supply from Standard Oil!

Currently, two icons of freebie marketing (sometimes called the "razor/blades model") would be Gillette and HP.

Competition is the main threat to freebie marketers. This strategy cannot success if cheaper alternatives to the complementary goods are available in the market; i.e., the company does not have a monopoly on these goods, which sometimes triggers legal issues.

One may also question the intrinsic sustainability of such a strategy. Even though the business model sounds great on paper, customers’ behavior may be a threat. As customers may realize that they make a gain (vs their perceived-price) when they purchase the main product, they may purchase the main product repeatedly, instead of keeping it… We all tend to renew our phone subscription whenever we have the opportunity, so that we can get a new phone for free!

Indeed, as far as electronics are concerned, freebie marketing tends to be inherently unsustainable. Indeed, when Lexmark and HP implemented it, new printers were expensive, and were kept for at least 5 years at the time. A decade later, as the price for printers dropped significantly, the results from this bound to be successful model started to dampen, as customers preferred purchasing a new printer to replacing their cartridge for nearly the same price…this reduced significantly printers’ useful life. Now, every time a new printer is sold, the manufacturer endures another negative-margin sale, and is deprived of the potential recurring revenue stream associated with the cartridge sales (as the older printer is not used anymore).

Interestingly enough, Kodak’s strategic focus is now in the opposite direction, as their 2009 marketing campaign shows.

Penetration pricing vs price skimming

When entering a new market, corporations face this dilemma: Should they hunt market share or per unit profit? Should they adopt a penetration pricing strategy, or should they use price skimming?

In a recent article, Hongju Liu explains that companies have incentives for both price skimming and penetration pricing. He takes the video games example, and analyses - based on pricing and strategic simulations - how the Nintendo 64 could have won the competition against the PS2. In reality, as mentioned previously, video game console manufacturers do use price skimming.

However, according to Hongju Liu's simulations, in a market where companies have a first move advantage, and experience network effects, there is an incentive for penetration pricing. However, if companies face consumer heterogeneity, then they have an incentive to price skim. If penetration pricing leads to a faster diffusion of the product and provides a first move advantage, it does so at the expense of lower initial profits, of a longer recovery of sunk costs, and of the capture of each segment’s surplus.

The issue of Internal Reference Price

The IRP is a core factor in customers’ buying process. This issue has already been the object of an extensive literature. According to most scholars, in their buying process, customers build their IRP based on past prices and on the contextual reference prices of related products (similar products on the shelf, for example).

Miao-Sheng Chen and Chaun-biau Chen, show in their article how the IRP can be used to influence consumer purchase behavior, and carry out an optimal price penetration strategy. Consumers perceive a gain if the price charged is below their IRP, and a loss otherwise.

Then, the issue, is to find a reliable and costless technique for your company to measure customers' IRP for a new or existing product. Joel E. Urbany and Peter R. Dickson show in their article that the most efficient way to measure IRPs is to estimate it from actual market prices. They explain that even though most consumers have a relatively poor knowledge of market prices, the benefits of extended studies to infer IRP from consumers' price perceptions are not worth the costs.

If measuring actual market prices does not provide the best estimate of the IRP, it does provide the most cost-efficient one, and the data collected can be completed launching various auctions on Ebay: the ending prices obtained provides a rather economical indication on how your product is perceived by customers.